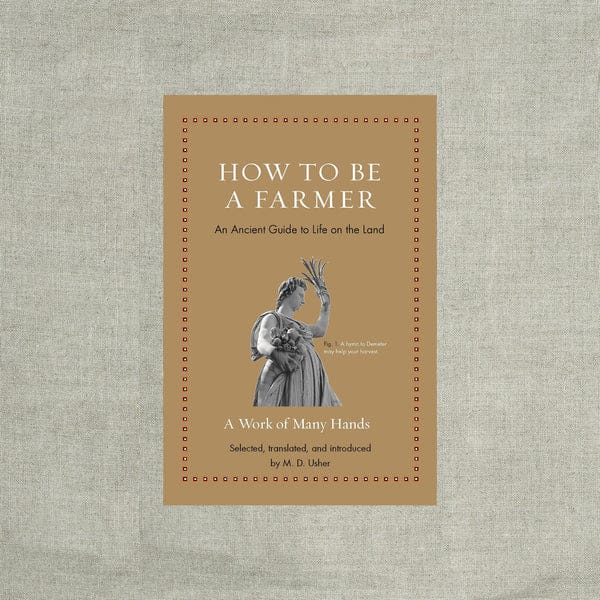

We sat with Mark Usher, French Institutes for Advanced Study Program (FIAS) Fellow at Iméra, to discuss his new book How to Be a Farmer, as well as Ancient wisdom to living closer to Nature.

—

In a hyper-digitalized era where many individuals grow “digital pets” and create “virtual gardens”, how can Roman and Greek literature and philosophy bring us back to the roots?

The ancient Greek and Romans were innocent of our technology-enhanced disconnectedness from Nature. They retained an “earthiness” and proximity to the sources of their survival that most people living in developed countries no longer possess today. Not only predigital (and pre-industrialized), the Ancients were also pre-capitalist, pre-reductionist, pre-postmodern, and pre-posthuman. They lived closer and with greater sensitivity to both the perils and prospects of their environments.

The poet Hesiod, for example, the first individual we can justly call an author, was a shepherd. Explain that away as a literary persona as much as you like, there’s no escaping the fact that shepherding is dirty, sometimes difficult work, as I can attest first-hand, and it requires a good deal of savoir-faire. There’s an authenticity I find in ancient writers that is refreshing and makes me more inclined to take to heart what they say. Even an elite like Julius Caesar, when not dividing Gaul into three parts, composed by dictation philosophical treatises in Greek (now lost) while riding long journeys on horseback. Riding a horse over long distances is tough going. So is composing philosophical works in Greek. Marcus Aurelius, who, as Roman emperor, was the most powerful man in the world at that time, wrote his famous Meditations in a tent while on campaign in the forests of Dacia. And it’s not just shepherds, generals, and emperors. Hipparchia of Maroneia, the first and perhaps only female Cynic philosopher, chose to live rough on the streets of Athens, despite an aristocratic upbringing, her actions a thoughtful protest against thoughtless social conventions.

As modern inheritors of their intellectual and cultural legacy, I think we have a lot to re-learn from the Ancients, and not only from their mistakes. As far as what the Greeks and Romans can teach us about getting back to the land, if that was the specific thrust of your question, have a look at the selections in my new book How to Be a Farmer and you’ll see for yourself!

How do you explore this philosophy of “living with nature” in your research project at IMÉRA “Urbs in Horto, Rus in Urbe”?

At Iméra I am developing ideas I first proposed in Plato’s Pigs and Other Ruminations: Ancient Guides to Living with Nature (Cambridge University Press, 2020): How should we choose to live in this new climatic regime, on a planet that is perhaps beyond its tipping point? To what sources for inspiration and guidance might we turn? I believe one such source is ancient Rome’s agrarian ethos of small, diversified farming.

Rus in urbe (“a bit of country in the city”), the second phrase in my project title, is reportedly what Nero called his infamous Golden House, a monstrosity of extravagant excess to create space for which the emperor firebombed the city and fiddled while it burned. Nero, of course, was an aberration, thankfully long gone. But the urge to re-create a lifestyle more closely connected to Nature (“a bit of country in the city”) was an urban-elite fantasy throughout the late Republic and early Empire, as it is for us today. Indeed, Romans of all sorts and at all periods in Rome’s history touted an ideology of smallholding and of getting back to the land. That’s one limb of my research.

The other phrase in my project title, Ubs in Horto (“a city within a garden”), is the motto of the city of Chicago and is the conceptual inverse of rus in urbe. Chicago is a sprawling metropolis that boasts ample parks and green spaces, hence the motto. But the idea behind the phrase is also metaphorical, that urban living can respond with symbiotic sensitivity to natural settings, including mental landscapes that embrace sustainable lifestyles lived in cooperation with Nature. On this score, I find the Cynics instructive.

I’ve just completed a book on this topic for Princeton, How to Say No: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Cynicism, which I’m polishing up here at Iméra and which will be coming out next year. I’m also working on a text by Dio Chrysostom (Discourse 7) about that author’s encounter with hill shepherds on the Greek island of Euboea who practiced a subsistence lifestyle of mixed agriculture, herding, and hunting. I argue that in describing their way of life (as an armchair anthropologist) Dio is in fact eulogizing these hill-folk as master practitioners of Cynic autarkeia (“self-sufficiency”). He views these Euboean peasants as wisely unencumbered by the politics, social follies, and materialistic cravings of the nearby town. I’ll be speaking about this at the Centre Paul-Albert Février in Aix-en-Provence on December 7th.

In short, though, I would summarize my work at Iméra as follows: Although “Nature” is an historically conditioned, polyvalent concept, it is applicable to both urban and rural settings. However we describe or understand it, Nature is our inescapable destiny since the biosphere is the ultimate source of any and all attempts to live ecologically meaningful lives—or indeed to live at all—be it in a garret apartment in Paris or on a farm in Provence. I say let’s come to terms with how to live in full accordance with it.

You’re a farmer and a professor of classical languages and literature and have often worked on interdisciplinary projects. Can you tell us more about your upcoming illustrated book?

Yes, I’m a farmer and Classicist, but also a hack of several other trades! You wouldn’t necessarily know it from my profile, but I’m first and foremost a servant of the Muses. I think the poetic impulse is what makes us distinctively human, so I’m a devotee. The book you are referring to, POEM: A Mashup, is due out this month (November 2021) with Fomite Press, a boutique publisher in my hometown of Burlington, Vermont. My collaborator, T. Motley, teaches comics and illustration at the School of Visual Arts in Manhattan. Several years ago, we published together The Golden Ass of Lucius Apuleius with David R. Godine, Tom illustrating my retelling of Apuleius’s classic, comedic novel.

This new illustrated book probes the questions: What makes poetry effective? How does a poem work? What are its goals and aims? Taking my cue from the musical form of mashup, I have composed what is known as a cento, stitching together snippets from famous English-language poems in such a way that the words of the text illustrate the aspect of poetry being described. The result is something of an “Ars Poetica” for a frenetic, digital age. A lively introduction and short, irreverent biographies of the poets featured in the book add to the fun. In Tom’s artwork, Word literally becomes Flesh, as letters emerge like epiphanies from the drawings. We think POEM is a unique achievement that stands in relation to canonical English-language poetry as Disney’s film, Fantasia, stands to classical music—first of its kind, something for all ages, and well worth experiencing again and again. With any luck readers will agree.

—

Mark Usher is Professor of Classical Languages and Literature and French Institutes for Advanced Study Program (FIAS) Fellow at Iméra, you can visit his profile here.